I once worked with a client in a very specific niche whose product was very similar to competitors’. In this scenario, price competition was an important factor for closing a sale.

At the time, one of this online store’s objectives was to improve the conversion rate. After some analysis, I identified difficulties involving users finding the desired product. To improve this, I recommended some interface improvements, such as adding new filters on category pages and also how some existing filters were displayed to the user.

Observing the metrics and through a heatmap tool (Hotjar), I noticed that this helped improve user navigation through the pages and made them find the product they needed much faster.

But the conversion rate didn’t improve. We increased investment in paid media, restructured the campaign differently, ran A/B tests, improved product descriptions, improved the category tree and still didn’t see improvement.

In one of these analyses I started to notice that the price for some types of products was very different compared to market leaders. But I needed to have an overview of the products and not just some random ones to be able to defend this price point, as it’s something delicate to approach.

And this is where I get to the main point of this article. To show you how I developed this competitor price study in an automated and fast way (at the time, the cost to hire a tool that performed this function was high and limited to a small number of products). In the topics below I detail the paths you should follow to do something for your scenario.

Additionally, at the end of the article I also provide a spreadsheet with an example of a simple HTML page that I built in the SEO lab we have at Ecto. For ethical reasons, this was the fairest way to teach this type of practice and also to not expose any store publicly. With this, you’ll be able to see the formula work on an online page (you can even try to extract other information as part of the study).

Another observation is that this tool ends up having certain limitations regarding the number of requests. I believe that something in the range of 50 products (and up to 3 competitors) should work well. More than that, I recommend using other page scraping methods.

For example, if you use Screaming Frog, it’s possible to do something similar, as it has the resource to extract information from the page and works with the same reference structure that I show in this article. If you master any programming language, know that there are some libraries like Scrapy or Selenium.

And keep in mind that you may need to make some adjustments over time, since websites undergo frequent improvements and code changes.

Extracting Product Prices via Google Sheets

Here there isn’t a magic formula that you can extract this information with a single XPath, like the examples I gave in the technical SEO validation articles and in how to extract URLs from an XML Sitemap, because each case ends up having some particularities. Therefore, my idea is to show some practical examples of online stores so you understand the idea and can adjust it to any case.

Store Example 1:

The code below I took from a store that sells water filters and uses a major e-commerce platform as its base:

<div itemtype="http://schema.org/Offer" itemscope="itemscope" itemprop="offers">

<link itemprop="availability" href="http://schema.org/InStock">

<meta content="BRL" itemprop="priceCurrency">

<meta itemprop="price" content="99.00">

</div>

This case above is the easiest for you to extract, as it uses structured product data in the page’s HTML, which facilitates building our XPath. For these cases, it would be:

//*[@itemprop='price']/@content

The good news is that the XPath above can work in various stores (although I said there wasn’t a magic formula, this is the one that comes closest), as it’s standard code and is inserted in most online platforms. Therefore, applying it in IMPORTXML we would have:

=IMPORTXML(url_monitorada;"//*[@itemprop='price']/@content")

Store Example 2:

Below, another code snippet extracted from a product page, now on a page that didn’t have structured data markup:

<div class="price-box minimalFlag">

<span class="regular-price" id="product-price">

<span class="price">R$479,00</span>

</span>

</div>

In this case, you need to build the XPath, as each store ends up having a different layout and consequently their own code structures. Based on the example above, we would have the following:

//*[@class='regularprice']/span[@class='price']/text()

Where the text() element informs that I only want the text (depending on the XPath it can return HTML code and that’s not our objective here). The previous elements inform a hierarchy in relation to the HTML structure and, in summary, detail the path to get there. The idea here is not to explain so much about XPath and if you want some examples, I recommend this XPath Cheatsheet (there you’ll find examples to extract various types of elements on a page).

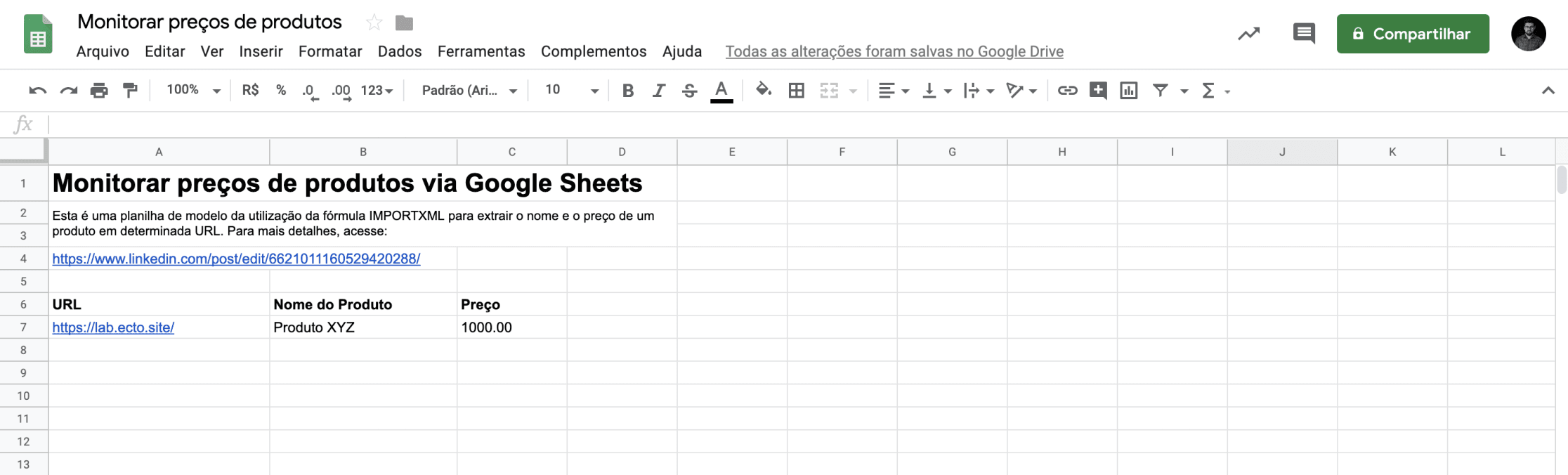

Template Spreadsheet

To facilitate your studies, I made an example spreadsheet:

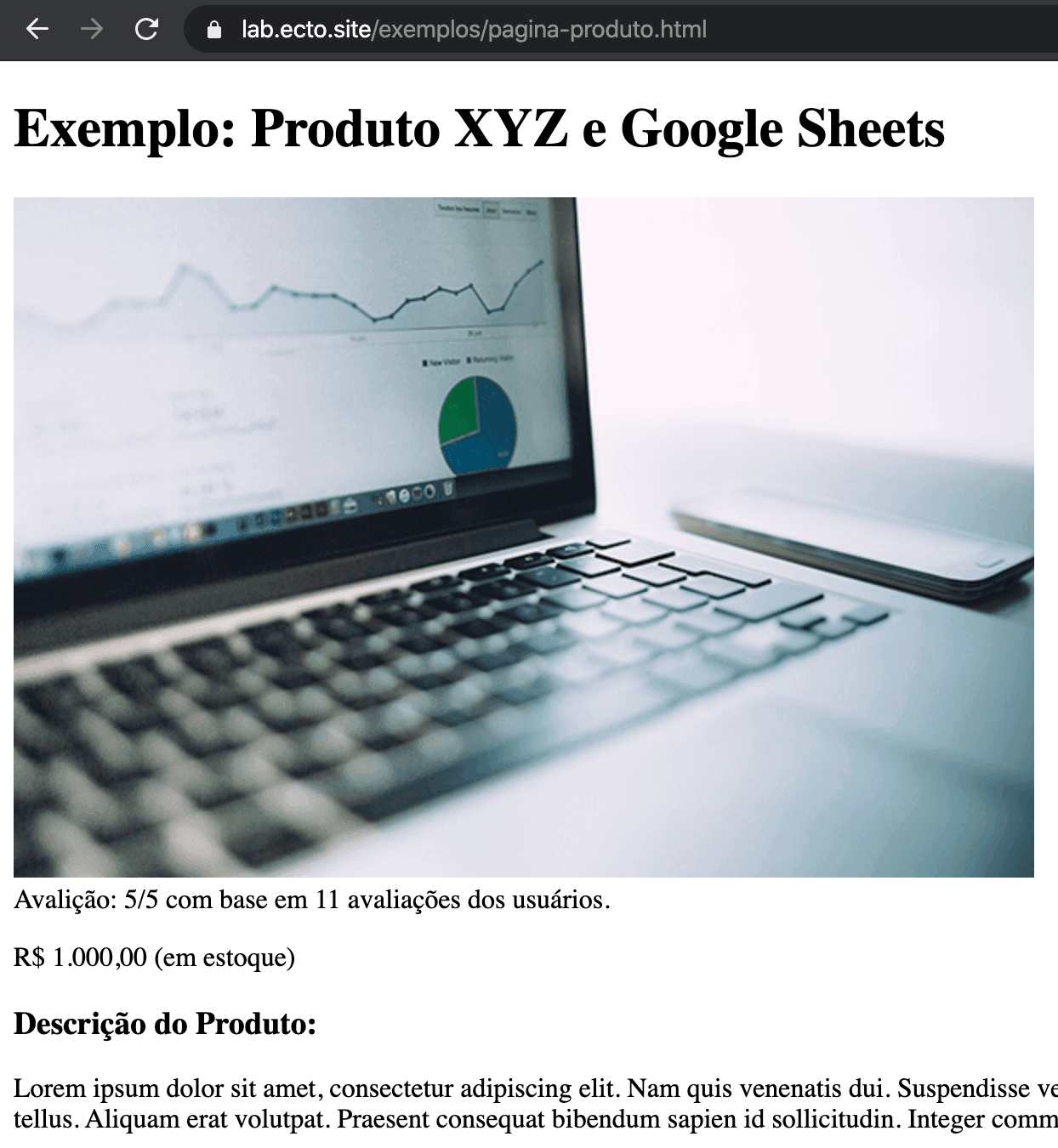

And as a bonus, I added an XPath to get the product name and also made a very simple page to display some product information for educational purposes in our SEO lab:

On this page there is other information you can practice extracting from the page such as: rating, description and page links.

Now, to structure your tracking spreadsheet, I recommend the following:

- Get all the URLs of the products from your store that you want to monitor.

- Do the same for your competitors.

- Organize the equivalent URLs in the spreadsheet.

- Tip: use conditional formatting and/or SUMIFS and/or COUNTIFS to group information (e.g.: how many products with higher prices, % of products above X dollars, etc.).

Share a bit of your experience with me! What did you think of this explanation format? Have you used this formula before? And if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask!